In my second year of university, I got to take a module called ‘Music and Social Change in Modern Britain.’ For a music lover, this was the perfect module to study, and in my time studying it I had the opportunity to write an extensive essay about music in modern Britain. I chose to write about the experiences of women and people of colour in Britain’s punk movement, and I thought that this would be the perfect place to share it.

The Punk movement in Britain in the 1970s was one that emerged in the shadows of a string of shifts; ranging between social, economic and political. This movement emerged in the wake of political, economic and social decline – a surge in violent crime (particularly that of a racist nature), staggering rates of unemployment and an overall distaste towards establishment. In the aftermath of the rock and roll music scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s, there simultaneously emerged a sense of disconnect between British working-class audiences and the rock symbols who found themselves indulging in financial prosperity following their success via means of consumerism. The culmination of such turbulent times and the desire for new cultural symbols to emulate the class struggle resulted in the emergence of the Punk movement. The British people felt disenfranchised; they were angry at the political, economic and social state of the country and wanted to rebel against the establishment that enabled rock musicians to prosper whilst they suffered – and thus the Punk movement was born.

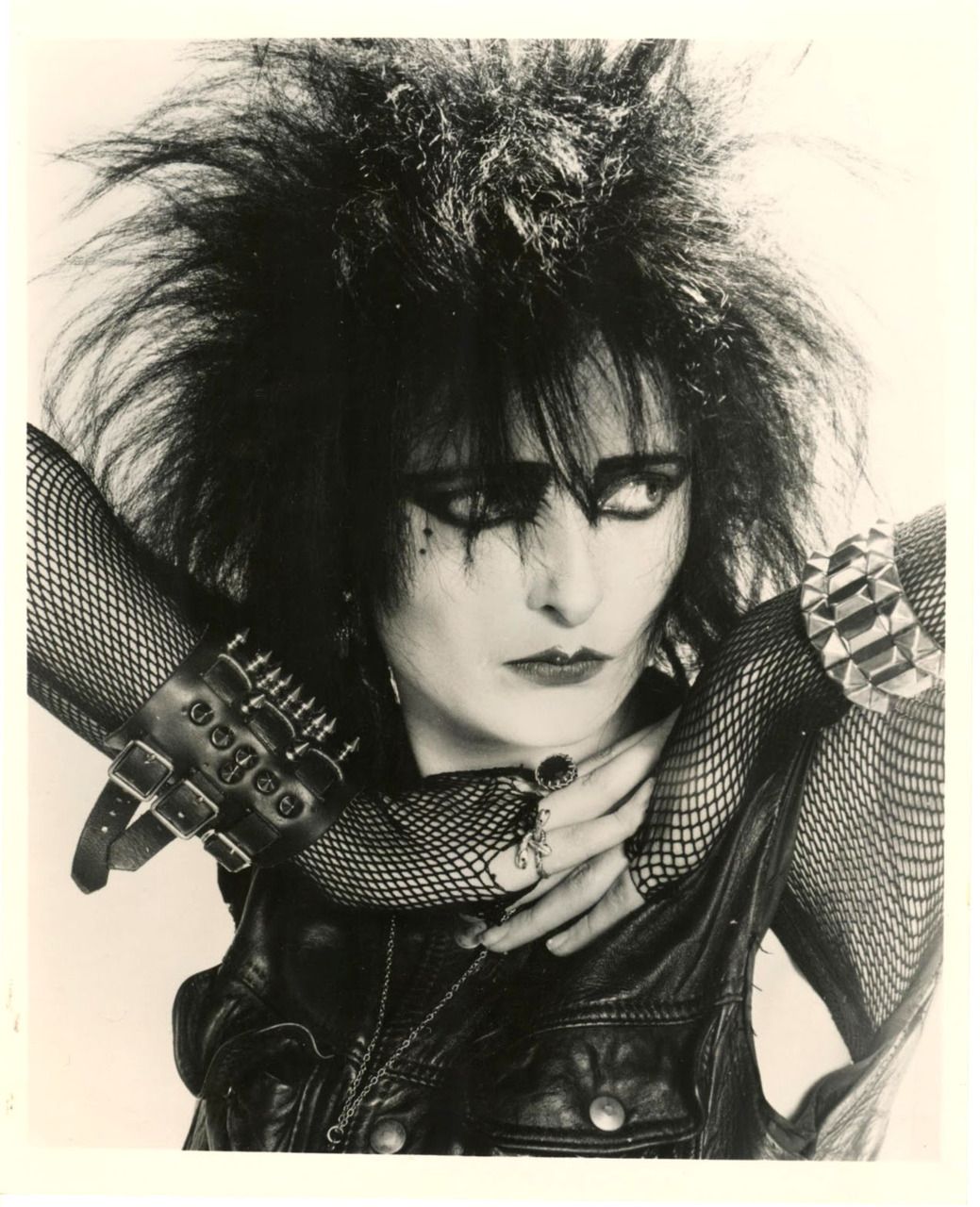

The Punk movement presented itself as an opportunity for British people to complain and to express their frustrations regarding issues at the time – yet one must consider how inclusive the movement itself was, most significantly when it came to the participation of women and people of colour. It can most certainly be said that the presence of women and people of colour amongst the Punk movement did indeed exist, especially through figures such as the Slits, Siouxsie and the Banshees, X-Ray Spex, The Specials and Basement 5[1]. Through the existence of prominent female bands, bands of mixed races and the outwardly acknowledged influence of reggae on the Punk movement, and Punk’s general anti-racist stance, it may be perceived to be open to the participation of both women and people of colour. However, this inclusivity had its limitations due to the Punk movement’s ambiguity when it came to political alignment, as well as the limitations placed on the careers of Punk women, stemming from the male domination of both the movement and the music industry itself. This essay shall therefore argue that the Punk movement presented itself as open to the participation of women and people of colour, yet the extent to which this participation was in fact accepted was limited.

For British women, the Punk movement presented itself as an opportunity to express themselves; punk was perceived as an anti-authoritarian, unconventional movement that women could interpret in any way that suited their needs. Matthew Worley asserts that “punk was soon recognised to have created a welcome opportunity for women to form bands and express their opinions”[2] and “it allowed women to contest perceived notions of sexuality and offered a space for women to perform and articulate an overtly feminist viewpoint.”[3] This belief that women used the Punk movement as a means of self-expression is ever present in lyrics produced by female-fronted bands: “Some people think that little girls should be seen and not heard / But I say oh bondage, up yours!”[4] (‘Oh Bondage! Up Yours!’ by X-Ray Spex); “Have a child to justify / Images that you apply / I won’t bow my head in shame.”[5] (‘Walls (Fun in the Oven)’ by Crass).

Women in Punk produced an abundance of lyrics of this nature, with the Slits’ ‘Typical Girl’ being memorialised as an anti-consumerism feminist anthem, decrying the stereotypical British women who “buy magazines” and “worry about spots.”[6] Lucy O’Brien succinctly encapsulates the freeing nature of the Punk movement for women, in stating that “Before the mid-1970s women who expressed seething anger were ostracised as misfits […] women were cutting and destroying the established image of femininity, aggressively tearing it down.”[7] The fact that Punk rooted itself in speaking out against grievances and using anger to produce meaningful music meant that women were provided with a space to express their feelings without consequence in a way that they previously could not.

Feminist takes placed against the raucous and loud instrumentals of Punk rock created what can be perceived as a branch off the feminist movement – “it reacted against, yet at the same time redefined 60s feminism.”[8] In rebelling against the expectations of women through means of music, content matter and physical appearance, women engaging with the Punk movement worked towards dismantling rigid stereotypes of previous eras and emancipating themselves from the belief that they were to be seen and not heard. Thus, the free and rebellious nature of the Punk movement meant that it was inherently open to the participation of women as it encouraged expression against preconceived notions of society at the time.

Whilst the expressive nature of the Punk movement enabled it to be perceived as open to the participation of women, as well as the prominence of women and female-fronted bands, the extent to which women were truly accepted amongst the Punk movement is debatable. It is true that Punk provided a space for women to angrily express their grievances, yet this space was not necessarily safe from misogyny and sexism that the late twentieth century was still wrought with. On a surface level, the perception of women in the Punk movement gave the movement itself some substance; it proved that the movement was dedicated to political expression through any means possible and encouraged the freedom of expression. Yet when it came to genuine, lucrative musical careers rather than simply creating and delivering a political statement, women suffered from the same restrictions that wider society had placed on them. Brian Cogan states that “contrary to myth, punk was not always women friendly […] the Slits suffered the same discrimination they had always done, treated as a novelty, a decoration, and not as serious contenders.”[9]

Quite ironically, in a subcultural movement that worked towards tearing down conventions and rebelling against the establishment, the Punk movement found itself upholding these archaic structures in its treatment of female musicians: “while punk arose to destroy convention, it was also mired in conventions and contradictions of its own.”[10] Despite female Punk artists producing feminist and anti-consumer anthems as contributions to the angry movement, it was the “capitalistic imperatives about marketability”[11] that held these women back from prospering and yielding the success that their male counterparts were achieving. Helen Reddington has addressed the sexist and repressive nature of the music industry throughout the Punk movement, and how this limited the success of women taking part in the movement. Reddington asserts that “all the media industry, apart from record-pluggers, were men […] and I think they [women] threatened men, or their reputation threatened men.”[12] Men were not used to these women being loud and direct with what they wanted – “the music industry was not ready for a cosmopolitan group of aggressive, politicised females.”[13]

Punk bands made up of women struggled to firmly place themselves within the music industry, with bands such as the Slits being quite late to signing a major label contract in comparison to their male counterparts. Despite the expressiveness and the freedom that Punk was observed to provide, it is inevitable that it would depend on capitalism in order to achieve longevity and to continue protesting the establishment. Women – particularly those who openly challenged preconceived notions of what it meant to be feminine – were not seen as lucrative investments in the Punk music industry. By not adhering to the expectations of women’s style and content, bands like the Slits were not considered to be marketable; sex and attraction sells, yet these women were using the space that Punk created to defy these rigid conventions regarding appearance.[14] This therefore indicates that the extent to which Punk was open to the participation of women was incredibly limited. As aforementioned, Brian Cogan stated that women in Punk were simply decorative to the movement[15]; their presence on the scene gave the movement an image of inclusivity, yet when it came to actually launching genuine music careers, this is where the sexist glass ceiling in Punk became clear: “the happy amateurs who took to the stage for fun or political expression were not so welcome if and when they began to take themselves seriously.”[16] The acceptance of women’s participation in the Punk movement was, ultimately, superficial.

Much like the consideration of women in the Punk movement, the presence of people of colour amongst the movement must be addressed. It is no surprise that people of colour as active performers in the Punk movement were incredibly limited, save for interracial bands such as The Specials or Basement 5, yet this is not to say that the participation of people of colour was necessarily opposed. Roger Sabin makes the bold statement that “punk was essentially solid with the anti-racist cause.”[17] Such a statement has found its base in the fact that Punk was very much engaged with both the reggae scene and the organisations Rock Against Racism (RAR) and the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) – clear symbols that Punk aligned itself with anti-racism and worked towards stigmatising racism in Britain.[18] Punk’s very ethos was to protest what was believed to be politically incorrect, and with the state of Britain at the time, racism fell into the long list of grievances that the Punk movement worked against. Thus, its engagement with organisations such as the Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League enabled the movement to drive home its anti-establishment, angry stance and to align itself with a cause.

This proclivity for standing alongside anti-racism has historically been evidenced by Punk’s tendency to incorporate reggae in its music scene. Punk bands such as the Clash, the Slits and Alternative TV infused reggae rhythms into their music, whilst Bob Marley reciprocated this appreciation through his song ‘Punky Reggae Party.’[19] In discussing the intricate relationship between the Punk movement and reggae, Dick Hebdige articulates that “reggae attracted those who wished to give tangible form to their alienation. It carried the necessary conviction, the political bite, so obviously missing in most contemporary white music.”[20] Jon Stratton goes further to argue that “there were increasingly visible challenges to the notion that Black people made Black music”[21] and that “Punk’s relationship with reggae music and West Indian culture […] was arguably an early exercise in multiculturalism.”[22] Alongside the Punk movement’s support of anti-racism, the infusion of reggae rhythms into punk music and the appreciation of Black artists indicates that Punk presented itself as open to the participation of people of colour, encouraging racial equality and somewhat paving the way for multiculturalism in the music industry, and subsequently British culture.

However, this very attraction that the Punk movement felt towards reggae music has proved to be problematic. As previously discussed, the Punk movement wished to align itself with any form of anti-establishment and encouraged the expression of grievances; ultimately, the Punk movement thrived off outrage. The close relationship that the Punk movement wished to portray with reggae and, subsequently, Black Britons, can be perceived as an attempt to profit off the struggle and strife associated with both reggae and the Black British community. Roger Sabin has addressed this phenomenon in stating that “the alliance was more often romanticised as ‘anti-authority’ than ‘anti-racist.’”[23] As a movement that was rooted in fighting against structural political oppression, leeching onto the anti-racist agenda simply provided the movement with further substance.

Sabin’s line of thinking is further emphasised through his assertion that the Punk movement found “romance”[24] in the Afro-Caribbean youth and their “reputation for being confrontational with the police.”[25] The idealisation of the struggle of Black Britons and the subsequent appropriation of reggae is even more damning when one considers that the Afro-Caribbean youth seemed to be the only subgroup of British people of colour that were deemed acceptable to participate in the Punk movement. Sabin suggests that Punk expressed an “almost total neglect of Britain’s Asians […] because the issue wasn’t a ‘hip’ one.”[26] Not only does this outline the extent to which Punk’s openness to the participation of people of colour was limited, but it also further portrays the way that it fed off of what was perceived to garner the most outrage and frustration towards the establishment – essentially, the Punk movement presented itself as open to participation of people of colour (specifically Black people) simply to provide substance for the movement.

The decorative nature of people of colour in the Punk movement is even more prevalent when considering the behaviours of Punk artists themselves. Siouxsie Sioux of Siouxsie and the Banshees was well known for sporting a swastika and doing right-armed salutes on stage, whilst Sid Vicious similarly wore a swastika t-shirt in the Jewish quarters of Paris.[27] Some Punk members were even openly hostile towards engagement in the Rock against Racism or the Anti-Nazi League, to which Sabin attributes to “punk’s broadly anti-authoritarian ethic […] there was a resentment of being seen as the ‘authentic voice’ of anything.”[28] Ultimately, the aim of the Punk movement was to shock and dismantle preconceived societal notions, and it would use whichever means were available to do so. Despite this, Punk’s desire to be both anti-authoritarian and unpredictable meant that it created not only an ingenuine approach to the question of racism, but it also established an ambiguous political stance which could easily be adapted to suit any agenda.

Jon Stratton discusses this ambiguity and states that “punk’s inherent whiteness could easily transform into a racist exclusivity,”[29] and this has been proved through what Matthew Worley describes as the far-right picking up on “aspects of punk’s language and imagery to reinforce – or signpost – opinions already held within the racist milieu.”[30] The unwillingness of Punk musicians to dismantle these problematic perceptions of the far-right in order to maintain an image of ambiguity with no restrictions ultimately meant that they enabled the movement to be used in fascist propaganda, and thus portrays how the participation of people of colour in the movement was limited. The superficial perception of the Punk movement held a lot more weight than genuine political activism did, and therefore it preferred to uphold agenda as opposed to addressing fundamental flaws of the movement.

On a surface level, the Punk movement was open to the participation of both women and people of colour. The presence of female-fronted bands such as the Slits and Siouxsie and the Banshees prove this, as does the emphasis on reggae roots’ influence on the musical side of the Punk movement. However, the fundamental flaws of the movement must be addressed – female Punk artists were ultimately unable to progress in the way that their male counterparts could, and the movement romanticised the struggle of Afro-Caribbeans in a way that seemed to piggyback off the reggae movement. The Punk movement based itself in ambiguity, unpredictability and appeared to have no rules, however it is this exact ideology that limits the extent to which women and people of colour were realistically allowed to engage in the movement. Historically, Punk has been mythologised as a ground-breaking anti-authoritarian, unconventional movement that provided a space for political expression, yet the way that it incorporated women and people of colour into its movement as aggressors for the anti-establishment ideology has proved to be superficial, thus indicating that the extent to which the Punk movement was open to the participation of both parties is substantially limited.

[1] Matthew Worley, ‘Shot by Both Sides: Punk, Politics and the End of Consensus’ in Contemporary British History, Vol. 26, Issue 3: Youth Culture, Popular Music and the End of ‘Consensus’ in Post-War Britain (Taylor & Francis, 2012) p. 338

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Vivien Goldman, ‘The Story of Feminist Punk in 33 Songs’ for pitchfork.com (2016) https://pitchfork.com/features/lists-and-guides/9923-the-story-of-feminist-punk-in-33-songs/ [Accessed on 25th April, 2020]

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Lucy O’Brien, ‘The Woman Punk Made Me’ in Punk Rock, So What?: the Cultural Legacy of Punk, eds. Roger Sabin (London: Routledge, 1999) pp. 191-93

[8] Ibid., p. 197

[9] Brian Cogan, ‘Typical Girls?: Fuck Off You Wanker! Re-Evaluating The Slits and Gender Relations in Early British Punk and Post-Punk’ in Women’s Studies, Vol. 41, Issue 2 (Taylor & Francis, 2012) p. 126

[10] Ibid., p. 133

[11] Ibid., p. 122

[12] Helen Reddington, The Lost Women of Punk Rock: Female Musicians of the Punk Era (Bristol: Equinox Pub, 2012) p. 184

[13] Brian Cogan, ‘Typical Girls?: Fuck Off You Wanker! Re-Evaluating The Slits and Gender Relations in Early British Punk and Post-Punk,’ p. 126

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Helen Reddington, The Lost Women of Punk Rock: Female Musicians of the Punk Era, p. 202

[17] Roger Sabin, ‘I Won’t Let That Dago By’ in Punk Rock, So What?: the Cultural Legacy of Punk, eds. Roger Sabin (London: Routledge, 1999) p. 199

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., p. 205

[20] Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London: Routledge, 1979) p. 63

[21] Jon Stratton and Nabeel Zuberi, Black Popular Music in Britain Since 1945 (London: Ashgate, 2014) p. 107

[22] Jon Stratton, When Music Migrates: Crossing British and European Racial Faultlines, 1945-2010 (London: Ashgate, 2014)p. 133

[23] Roger Sabin, ‘I Won’t Let That Dago By’ p. 205

[24] Ibid., pp. 203-204

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid., p. 208

[28] Ibid., pp. 206-207

[29] Jon Stratton, When Music Migrates, p. 128

[30] Matthew Worley, ‘Shot by Both Sides,’ p. 337